Fundamentalism, conceit, and eschatology

'Been reading Fr. Richard P. McBrien's 1344-paged tome, Catholicism (New Study Edition). Father Mcbrien is Crowley-O'Brien-Walter professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame. It is noteworthy that the book is printed without an imprimatur. A section of interest so far:

The Second Vatican Council, in the same Pastoral Constitution, appropriately viewed the crisis of modernization as a special opportunity for the Church. In the face of such developments, it is said, more and more people are raising the most basic questions about the meaning of life and raising them with a new sharpness and urgency: "What is humanity? What is this sense of sorrow, of evil, of death, which continues to exist despite so much progress? What is the purpose of these victories, purchased at so high a cost? What can we offer to society, what can we expect from it? What follows this earthly life?"

Fundamentalism

But not everyone shares the positive and even optimistic outlook of the council's Pastoral Constitution, Gaudium et spes ("Joy and Hope"). Modernity's most determined adversary is fundamentalism, whose face is both Catholic and Protestant, Christian and non-Christian. According to two scholars who have made the most extensive study of worldwide fundamentalism, religious fundamentalisms are "movements that in a direct and self-conscious way fashion a response to modernity" (Martin E. Marty and R. Scott Appleby, The Glory and the Power: The Fundamentalist Challenge to the Modern World, Boston: Beacon Press, 1992, p. 10). It is not that fundamentalists reject all of the products of modernity. They take full advantage of its remarkable achievements in transportation, communications, medical science, and the like. But they are antagonistic towards the values that seem to accompany these advances. One such value is the superiority of reason over revelation as a means of knowledge; another is the superiority of freedom over an imposed conformity of thought and behavior.

Not until modernity made inroads into religious communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did fundamentalism emerge as a major force within the churches, first within Protestantism, more recently within Catholicism, and eventually within Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and other non-Christian religions. The fundamentalists viewed religious modernists as carriers of the dreaded disease of secular modernism from the outside world. But the religious modernists were regarded as more dangerous than secular modernists because they could manipulate the community's religious symbols and practices from within.

Unlike religious conservatives who are content to keep modernism at arm's length while recommitting themselves to traditional teachings and practices, fundamentalists dig in their heels and fight back. "That is their mark," Marty and Appleby observe. "They want to reclaim a place they feel has been taken from them. They would restore what are presumed or claimed to be old and secure ways retrieved from a world they are losing. Fundamentalism will do what it takes to assure their future in a world of their own defining" (17).

Such a world-building endeavor requires charismatic and authoritarian leadership, as well as a disciplined inner core of staff and a large group of sympathizers. All follow a rigorous sociomoral code that sets them apart from nonbelievers and from compromisers within the fold. Fundamentalists set boundaries, name and investigate their enemies, seek recruits and converts, and often imitate the very forces they oppose. "Fundamentalism is, in other words, a religious way of being that manifests itself as a strategy by which beleaguered believers attempt to preserve their distinctive identity as a people or group" (34).

Thomas F. O'Meara, O.P., provides a description and critique of Catholic fundamentalism in his Fundamentalism: A Catholic Perspective (1990). Catholic fundamentalism, he suggests, is a corruption of Catholic values, especially of sacramentality. It sees the world as evil and dangerous, forgetting that God is its Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier. It limits the manifestation of grace to the extraordinary and even the bizarre, forgetting that God is present to ordinary people, in ordinary situations of life. And it limits access to God's grace to a chosen few, the righteous within the larger community of the unrighteous, forgetting that God wishes to save all and has won salvation for all in the redemptive work of Jesus Christ (80-93).

Catholic fundamentalism has two forms: biblical and doctrinal. Catholic biblical fundamentalism, like Protestant biblical fundamentalism, interprets Scripture "literally" and selectively. But Catholic proof-texts differ from Protestant proof-texts. For Catholics, "You are Peter . . ." (Matthew 16:18-19) is the hermeneutical prism through which all else in the Bible is to be read. Catholic doctrinal fundamentalism interprets the official teachings of the Church "literally" (which is to say unhistorically) and selectively. Like worldwide fundamentalism, Catholic fundamentalism tends to be militant in style, and more antagonistic to the "enemies within" than to those outside.

The council's Pastoral Constitution urges a different approach. The Church's mission "to shed on the whole world the radiance of the gospel message, and to unify under one Spirit all people of whatever nature, race, or culture" requires that within the Church itself there be "mutual esteem, reverence, and harmony" and a "full recognition of lawful diversity." This imposes upon all members the need for dialogue. "For the bonds which unite the faithful are mightier than anything which divides them. Hence, let there be unity in what is necessary, freedom in what is unsettled, and charity in any case." (92-5)

Thomas F. O'Meara's critique and description of fundamentalism struck me in particular, not with Catholic fundamentalism (which I admit I have never encountered), but with the more common--and virulent--strain: Protestant fundamentalism. In my (limited) experience with a significant number of Protestant churches, in particular, evangelical types, O'Meara's words fit their practices to a T. They preach a world view of the physical realm as a constant battleground between good and evil, where, lurking behind every corner, is Satan ready to trip them, tempt them with sin, ensnare their souls, and cart them off to Hell.

Not to contribute any more to the existing schism, but I have two major problems with this doctrine: to the pastor and other church leaders, "Are you preaching salvation and grace, or are you marketing fear?" I must admit the "fire and brimstone" approach never did much for me. Secondly, such an approach, I suspect, subtly appeals to--and indulges in--an unacknowledged narcissism in the congregation. I.e. "Oh, look at me! I am so important--my soul is so important--that Satan himself has to brainstorm 24/7 to try and sway me over to his side!" Oh, the conceit! Sorry to burst your bubble, my liege, but, chances are, you are just a 9-to-5 Joe Blow or plain Jane on a planet with 6.5+ billion other humans. Even if the Devil, over-clocking his neurons, manages to sway you over to the dark side, you will never be in a position to inflict the type of harm and evil as say, Adolf Hitler or Pol Pot. The pinnacle of your criminal career--should you turn evil--is probably the ignominy of being tackled and handcuffed on "COPS."

Even then, Erik Cartman will receive more airtime in his 5 minutes as Hitler than you.

Oh, the sheer audacity of imagining God and Satan locked in one titanic struggle after another, in a bid for your priceless soul!

In your dreams, pal.

Get over yourself. You are not that important.

"Oh! I'm constipated this morning! Oh lawdy! The Devil is after me!"

"No, dumbass. He isn't. Eat more vegetables."

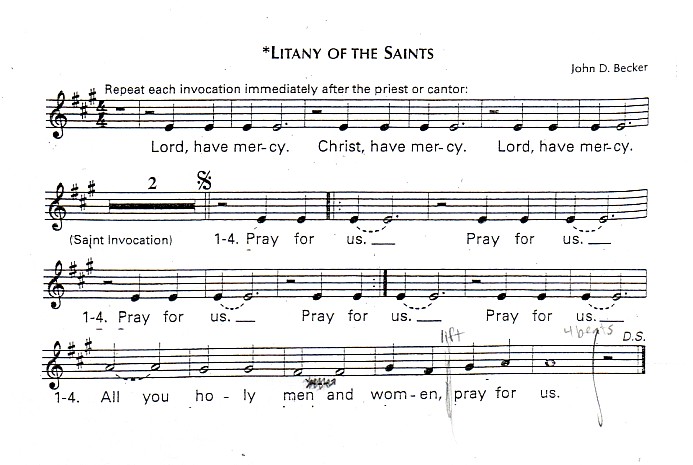

The other problem, not mentioned in the quoted passage, is the eschatological bent in many of these churches. Every Sunday, they close their eyes, and submitting to a tide of mass hysterics, sing about how this world sucks / blows, and they can hardly wait to leave this all behind.

Newsflash I: God created this world. It is not all evil. Do some good while you are down here, ya? Closing your eyes, wishing it, and singing about it isn't going to bring about your journey much sooner.

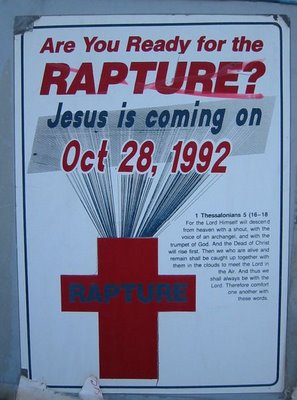

Newsflash II: This fixation with eschatology isn't anything new. It has been done before:

Christians in the 1st century AD believed the end of the world would come during their lifetime. Jesus in Mark 13:8 compared the end of the world with a mother's birth pain, and the image implied the world was already pregnant with its own destruction, but no one but God knows when it will happen. When the converts of Paul in Thessalonica were persecuted by the Roman Empire, they believed the end was upon them. However, doubt rose when as early as the 90s Christians said, "We have heard these things [of the end of the world] even in the days of our fathers, and look, we have grown old and none of them has happened to us". In the 130s Justin Martyr declared God was delaying the end of the world because he wished for Christianity to become a world religion. In the 250s Cyprian wrote that Christian sins of that time were a prelude and proof that the end was near.

However, by the 3rd century most Christians believed the End was beyond their own lifetime; Jesus, it was believed, had denounced attempts to divine the future, to know the "times and seasons", and such attempts to predict the future were discouraged; yet the End was given a date with the help of Jewish traditions in the Six Ages of the World. Using this system, the End was fixed at 202, but when the date passed, the date was changed to AD 500. After AD 500 the importance of the End as a part of Christianity was marginalized, though it continues to be stressed during the season of Advent. (Source)

Also, check this out: Timeline of unfulfilled Christian Prophecy.

Anyone remember the proclamations that the end is nigh around 1999? And then when it didn't, they came up with some crazy explanation that it is actually 2001 because of the way the years are counted. And then when 2001 rolled along, they all disappeared into the woodwork.

More here, from Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

The danger of fixating on the endtimes is this: what happens when it doesn't end?? History is rife with examples of religious sects that, having predicted the endtimes, and discovering that it didn't arrive as promised, chose to bring about their own: Jim Jones with 914 of his followers in the jungles of Guyana ; the Japanese doomsday cult, Aum Shinrikyo, which decided to bring some of their fellow japanese citizens along with them by releasing sarin gas in the subway; 48 members of the Order of the Solar Temple were dressed in ceremonial robes, had plastic bags over their heads, and each shot in the head; other members were shot, poisoned or smothered; Heaven's Gate, the UFO cult, whose followers wore Nike shoes, drank cocktails of phenobarbital and vodka, and put plastic bags over their heads so that their souls could be picked up by the "mothership" hiding behind Comet Hale-Bopp; the list goes on.

You are here for the time being.

Make this world a better place.

And you can see them there,

On Sunday morning

They stand up and sing about

what it's like up there

They call it paradise

I don't know why

You call someplace paradise,

kiss it goodbye

("The Last Resort," The Eagles)