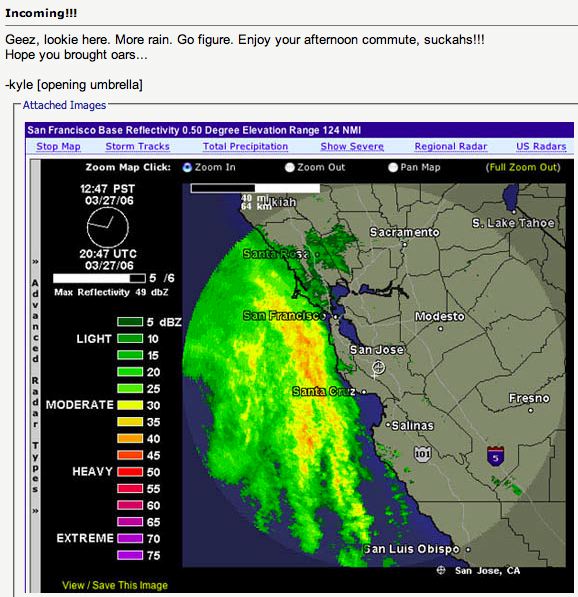

Without Roots: The West, Relativism, Christianity, Islam

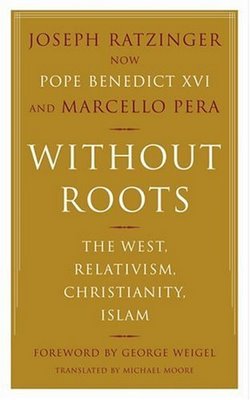

After realizing that kyle's cheerful forecast is going to extend into the next week, I picked up one of the books featured in Amy Proctor's post, It's the Demography, Stupid. Thanks, Amy : )

This slim volume packs a potent punch. My experience of reading this book can be liken to that of a man, cold, lonely, and hungry in a forest, walking into a camp with a roaring fire, hot food, and warm hospitality--for both Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) and Marcello Pera share my disquietude with the plague of relativism and political correctness that has rotted family, society, academia and country. The people may protest en mass for free speech, but individually, they are stifled by the specter of political correctness. Afraid of offending the sensibilities of others, they do not speak their true minds. Afraid of hurting the feelings of others, they dare not assert or embrace clear and definite positions, but instead waffle around in a vague, wishy-washy dance of relativism--in delusional hopes that it leads to the utopia promised by pacifism and capitulation.

From the Executive Officer at CERC:

In May 2004, retired professor of philosophy and now president of the Italian Senate, Marcello Pera, addressed the Lateran Pontifical University. The following day, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger spoke to the Italian Senate.

The perspectives advanced by these two men dovetailed beautifully and their speeches, along with an exchange of letters between the two men, now comprise the small volume, Without Roots: The West, Relativism, Christianity, Islam, just released from Basic Books

This is by no means a comprehensive book review. Nor is every passage deemed worth quoting included (not only would that be tedious, but possibly illegal). What is offered then, are sections salient to my peculiar affinities.

From the foreword by George Weigel:

"Crisis" is an overused word these days, but in the present circumstances of Europe it is, unfortunately, appropriate. Europe, Joseph Ratzinger writes, has become hollowed out from within, paralyzed in its culture and its public life by a "failure of its circulatory system." And the results of that hollowing-out are most evident in the unprecedented way in which Europe is depopulating itself. Generations after generations of below-replacement-level birthrates have created a demographic vacuum which, like all other vacuums in nature, is not remaining unfilled: the vacuum is being filled by transplanted populations whose presence in Europe is a challenge to Europe's identity, and could become a threat to European democracy. (viii - ix)

Marcello Pera's lecture, "Relativism, Christianity, and the West":

The thinking that currently prevails in the West regarding the universal features of the West is that none of them has universal value. According to the proponents of these ideas, the universality of Western institutions is an illusion, because in reality, they are only one particularity among many, with a dignity equal to that of others, and without any intrinsic value superior to that of others. Consequently to recommend these institutions as universal would be a gesture of intellectual arrogance or an attempt at cultural hegemony, imposed by arms, politics, economics, or propaganda. Moreover it only goes to follow that seeking to export these same institutions to cultures or traditions that are different from our own would be an act of imperialism.

[ . . . ]

One particularly revealing symptom shows the extent to which this mixture of timidity, prudence, convenience, reluctance, and fear has penetrated the fiber of the West. I refer to the form of self-censorship and self-repression that goes by the name of political correctness. "P.C." is the newspeak that the West uses nowadays to imply, allude to, or insinuate rather than to affirm or maintain.

We read and hear this newspeak every day. According to its dictates, everything can be compared and evaluated within the confines of Western culture--be it Coca-Cola with Chianti, Gaudí with Le Corbusier, Darwinism with intelligent design--and many comparisons can be made between aspects of Western culture and their counterparts in other cultures, such as hospitality, social customs, individual behavior, clothing, and so forth. Yet should one attempt to place in a hierarchical order these cultures or civilizations [. . .] or to simply organize them according to a scale of preferences, from better to worse, out pop self-censorship, prohibitions, and linguistic restraints. Consequently, as one can easily document in today's newspeak, whenever a culture lacks or flatly rejects our institutions, we are not allowed to say that our own culture is better or simply preferable. The only thing that politeness allows us to say is that cultures and civilizations are different.

To me this form of linguistic re-education is unacceptable. I reject it on moral grounds, which are the ultimate* reason for refuting an intellectual position.

*To whoever might take issue with my use of the word "ultimate," I would point out that we reject Nazism, fascism, communism, racism, anti-Semitism, and fanaticism not because they conflict with some logical theorem, or because they are empirically or scientifically false, but because they offend our consciences, contradict our deep intuitions about human rights, and violate our fundamental values. We reject them, in other words, for practical rather than theological reasons.

[ . . . ]

The world is filled concern but also with hypocrisy. Hypocrisy on the part of people who see no evil and speak no evil to avoid becoming involved; who see no evil and and speak no evil to avoid appearing rude; who proclaim half-truths and imply the rest, to avoid assuming responsibility. These are the paralyzing consequences of the "political" correctness (as well as intellectual, cultural, and linguistic correctness) that I reject. (3-7)

The section, "The Double Paralysis of the West," bears enough import to be quoted in its entirety:

After years of virtual or remote anthropology exercises conducted by philosophers and scientists to prove that cultures cannot be arranged in hierarchical order, the case of Islam is finally real, at hand, and ever present.

In 1992, a French expert on Islam, Oliver Roy, wrote that "Political Islam cannot resist the test of power. . . . Islamism has been transformed into a neo-fundamentalism that only cares about re-establishing Islamic law, the sharia, without inventing new political forms." As proof, he pointed to a long list of shortcomings and failures. Islam has not produced its own political model, economic system, autonomous public institutions, division between family and the state, equal rights for women, or community of states founded on anything except religion. In other words, he considered Islam a failure. Rather than open itself up to new prospects, "The Islamic parenthesis has closed a door, the door of the revolution and the Islamic state."

I wonder whether the thesis of Oliver Roy, and of so many Westerners who are thinking along the same lines, is true or false. If it is true, can one then say that the Western model is better than the Islamic one?

The response to the first question depends solely on empirical research and analysis. The response to the second question does not, mainly because it patently expresses an evaluation ("better"). At this point, it would be useful to make a preliminary distinction: the difference between making a judgment and making a decision; in other words, the difference between affirming a thesis--in this case a value thesis of the type "A is better than B"--and taking a stand, in this case a political stand of the type "follow A," "fight against B." The two questions are related, although not in a logical, deductive manner. To argue that the model of Western democratic institutions and rights is better than the Islamic model does not imply taking any particular course of action. One could say that the West is better than Islam and still tolerate Islam, respect Islam, dialogue with Islam, ignore Islam, or even obstruct Islam, clash with Islam, among the many possible stances. According to the old proverb, it's one thing to say, another to do. To rephrase this proposition in logical terms, there are no formal implications between "is" and "ought" (ab esse ad oportere non valet consequentia, as one says in Latin).

The dominant culture in the West, however, thinks the opposite, and reveals its prejudices through a major flaw in reasoning. It thinks that "ought" descends from "is." According to this way of thinking, if a person maintains that the West is better than Islam--or, to be more specific, that democracy is better than theocracy, a liberal constitution better than sharia, a parliamentary decision better than a sura, a civil society better than an umma, a sentence by an independent tribunal better than a fatwa, citizenship better than dhimma, and so forth--then he or she ought to clash with Islam. This is an error of logic that compounds the error of believing that our institutions have no right or basis to be proclaimed as universal.

The consequence of these two errors is that today the West is paralyzed twice over. It is paralyzed because it does not believe that there are good reasons to say that it is better than Islam. And it is paralyzed because it believes that, if it such reasons do exist, then the West would have to fight Islam.

I personally reject these positions. I deny that there are no valid reasons for comparing and judging institutions, principles, and values. I deny that such a comparison cannot conclude that Western institutions are better than their Islamic counterparts. And I deny that a comparison will necessarily give rise to a conflict. I do not deny, however, that if an offer to dialogue is responded to with a conflict, then the conflict should not be accepted. For me, the opposite holds true. I affirm the principles of tolerance, peaceful coexistence, and respect that are characteristics of the West today. However, if someone refuses to reciprocate these principles and declares hostility or a jihad, I believe we must acknowledge that this person is our adversary. In short, I reject the self-censorship of the West. (bold face mine 7-10)

A common point between Pera and Ratzinger in their lectures (and letters) is the moral bankruptcy--and consequently, physical paralysis-- that relativism inevitably spirals into. When one thing is as good as the other, there is nothing to stand for, nothing to fight for.

[T]he relativism that preaches the equivalence of values or cultures is grounded not so much in tolerance as in acquiescence, more inclined toward capitulation than awareness, more focused on decline than on the force of conviction, progress, and mission (which were once typical of Christianity, Europe, and the West). (34)

But do not misunderstand me, either deliberately or through distraction. I am not advocating a Western declaration of war or state of war. I am advocating something else that to me seems even more important. I am urging people to realize that a war has indeed been declared on the West. I am not pushing for a rejection of dialogue, which we need more than ever with those Islamic countries that wish to live in peaceful coexistence with the West, to our mutual benefit. I am asking for something more fundamental: I am asking for people to realize that dialogue will be a waste of time if one of the two partners to the dialogue states beforehand that one idea is as good as the other. (bold face mine 45)

Marcello Pera is non-Catholic and a secularist, by the way.

In "The Spiritual Roots of Europe: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow," Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI ) went from the accounts of Herodotus (484 - 425 BC) and the transfer of the Roman Empire capital to Constantinople (330), to the Reformation (1517) and the French Revolution (1789 - 1799) in twelve pages. And you thought the Enzo was fast...

At the hour of its greatest success, Europe seems hollow, as if it were internally paralyzed by a failure of its circulatory system that is endangering its life, subjecting it to transplants that erase its identity. At the same time as its sustaining spiritual forces have collapsed, a growing decline in its ethnicity is also taking place.

Europe is infected by a strange lack of desire for the future. Children, our future, are perceived as a threat to the present, as if they were taking something away from our lives. Children are seen as a liability rather than a source of hope. There is a clear comparison between today's situation and the decline of the Roman Empire. In its final days, Rome still functioned as a great historical framework, but in practice it was already subsisting on models that were destined to fail. Its vital energy has been depleted. (66-7)

The communist systems collapsed under the weight of their own fallacious economic dogmatism. Commentators have nonetheless ignored all too readily the role in this demise played by the communists' contempt for human rights and their subjugation of morals to the demands of the system and the promises of the future. The greatest catastrophe encountered by such souls was not economic. It was the starvation of souls and the destruction of the moral conscience.

The essential problem of our times, for Europe and for the world, is that although the fallacy of the communist economy has been recognized--so much so that former communists have unhesitatingly become economic liberals--the moral and religious question that it used to address has been almost totally repressed. The unresolved issue of Marxism lives on: the crumbling of man's original uncertainties about God, himself, and the universe. The decline of a moral conscience grounded in absolute values is still our problem today. Left untreated, it could lead to the self-destruction of the European conscience, which we must begin to consider as a real danger--above and beyond the decline predicted by Spengler*. (73-4)

*The obligatory reference here is to the following words of Erwin Chargaff: "Where everyone is free to play the lion's part--in the free market, for example--what is attained is the society of Marsyas, a society of bleeding cadavers."

We do not need to look far for examples to Chargaff's point: people piling upon each other with frivolous lawsuits; companies doing the same. Corporations gouging consumers. Consumers retaliating through software, music, video piracy, and even fraud. Where is that sense of "core values" which form the bedrock of one's existence and actions in life? Most of the time, all that is observed (and encountered) is the attitude of "Me! Me! Me! What's in for me?"

I must admit I am enamored by the manner in which Cardinal Ratzinger conveys his thoughts--he does not mince his words, and he saves the best for last:

The final element of the European identity is religion. I do not wish to enter into the complex discussion of recent years, but to highlight one issue that is fundamental to all cultures: respect for that which another group holds sacred, especially respect for the sacred in the highest sense, for God, which one can reasonably expect to find even among those who are not willing to believe in God. When this respect is violated in a society, something essential is lost. In our contemporary society, thank goodness, anyone who dishonors the faith of Israel, its image of God, or its great figures must pay a fine. The same holds true for anyone who dishonors the Koran and the convictions of Islam. But when it comes to Jesus Christ and that which is sacred to Christians, instead, freedom of speech becomes the supreme good. The argument has been made that restricting freedom of speech would jeopardize or even abolish tolerance and freedom overall. There is one major restriction on freedom of speech, however: it cannot destroy the honor and the dignity of another person. Lying or denying human rights is not freedom.

This case illustrates a peculiar Western self-hatred that is nothing short of pathological. It is commendable that the West is trying to be more open, to be more understanding of the values of outsiders, but it has lost all capacity for self-love. All it sees in its own history is the despicable and the destructive; it is no longer able to perceive what is great and pure. What Europe needs is a new self-acceptance, a self-acceptance that is critical and humble, if it truly wishes to survive.

Multiculturalism, which is so constantly and passionately promoted, can sometimes amount to an abandonment and denial, a flight from one's own heritage. However, multiculturalism cannot survive without common foundations, without the sense of direction offered by our own values. It definitely cannot survive without respect for the sacred. Multiculturalism teaches us to approach the sacred things of others with respect, but we can only do this if we, ourselves, are not estranged from the sacred, from God. We can and we must learn from that which is sacred to others. With regard to others, it is our duty to cultivate within ourselves respect for the sacred and to show the face of the revealed God . . .. (bold face mine 78-9)

What follows after the text of the lectures by Marcello Pera and Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger is an exchange of letters between the two men.

From Marcello Pera to Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger:

Europe is infected by an epidemic of relativism. It believes that all cultures are equivalent. It refuses to judge them, thinking that to accept and defend one's own culture would be an act of hegemony, of intolerance, that betrayed an anti-democratic, anti-liberal, disrespectful attitude towards the autonomy of other populations and individuals. To a Europe that thinks along such lines, the word "spiritual" is palatable because it is so generic, as is the word "religious," because it is vague, obvious, and widely shared. The word "Christian," by contrast, is considered unacceptable, because it is an identifying adjective: appropriate, precise, and therefore suspected of arrogance.

[ . . . ]

I fear that Europe has not realized this. And thus, I fear that European pacifism, however noble and generous it may be, is not so much a realistic, mediated, conscious choice as a heedless, passive consequence of its angelic relativism. This is why I speak of the spirit of Munich, which has an additional irritant today. Namely, that relativism, after teaching that all cultures and all civilizations are equal, makes the contradictory insinuation that our culture and our civilization are worse than others. Hence, there has been a spread--especially throughout Europe--of a sense of guilt, of self-flagellation, of a need for forgiveness from which not even the Church is exempt, together with a feeling of smugness over the dangers avoided. That September 11 atrocity? Blame it on our own genocidal acts, says Chomsky. Suicide bombs? Our fault: We have reduced the Palestinians to desperation, says Saramago. And so on, accompanied by a crescendo of breast-beating. How can we restore realism to a Europe that thinks along such lines? (85-94)

With his trademark assertiveness (during his position as a head of Doctrine and Faith, under the late John Paul II, some of his fans affectionately dubbed him, the "intellectual pit bull of the Church"), Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger pulls no punches in his reply:

You and I are of a single mind in rejecting a pacifism that does not recognize that some values are worthy of being defended and that assigns the same value to everything. To be in favor of peace on such a basis would signify anarchy, which is blind to the foundations of freedom. Because if everyone is right, no one is right.

[ . . . ]

I would now like to say a few words about relativism. As I said at the outset, I am most grateful for all that you explained so carefully in your lecture, and I agree with you completely.

In recent years I find myself noting how the more relativism becomes the generally accepted way of thinking, the more it tends towards intolerance, thereby becoming a new dogmatism. Political correctness, whose constant pressures you have illuminated, seeks to establish the domain of a single way of thinking and speaking. Its relativism creates the illusion that it has reached greater heights than the loftiest philosophical achievements of the past. It prescribes itself as the only way to think and speak--if, that is, one wishes to stay in fashion. Being faithful to traditional values and to the knowledge that upholds them is labeled intolerance, and relativism becomes the required norm. I think it is vital that we oppose this imposition of a new pseudo-enlightenment, which threatens freedom of thought as well as freedom of religion. (bold face mine 107-8; 127-8)

Near the end of his lecture, Marcello Pera shares his disturbing prognostication:

A foul wind is blowing through Europe. I am referring to the idea that all we have to do is wait and our troubles will disappear by themselves, so that we can afford to be lenient even with people who threaten us, and that in the end, everything will work out for the best. This same wind blew through Munich in 1938. While the wind might sound like a sigh of relief, it is really a shortness of breath. It could turn out to be the death-rattle of a continent that no longer understands what principles to believe, and consequently mixes everything together in a rhetorical hodgepodge. A continent whose population is decreasing. A continent whose economy cannot compete. A continent that does not invest in research. That thinks that the protective social state is an institution free of charge. That is unwilling to shoulder the responsibilities attendant upon its history and its role. That seeks to be a counterweight without carrying its own weight. That, when called upon to fight, always replies that fighting is the extrema ratio, as if to say that war is a ratio that should never be used. (43)

Notes

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, was the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under the late Pope John Paul II, and has long been regarded as one of the most profound Catholic theological and spiritual writers of our times. His numerous books include God and the World, Introduction to Christianity, Salt of the Earth, and The Spirit of Liturgy

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, was the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under the late Pope John Paul II, and has long been regarded as one of the most profound Catholic theological and spiritual writers of our times. His numerous books include God and the World, Introduction to Christianity, Salt of the Earth, and The Spirit of Liturgy Marcello Pera, a professor of the philosophy of science at the University of Pisa, is president of the Italian Senate. He divides his time between Rome and Lucca in Italy.

Marcello Pera, a professor of the philosophy of science at the University of Pisa, is president of the Italian Senate. He divides his time between Rome and Lucca in Italy.Michael F. Moore is the official translator of the Italian Mission to the United Nations and the chairman of the Translation Committee of the PEN America Center. He lives in New York City.

George Weigel, a Roman Catholic theologian and one of America's most distinguished public intellectuals, has written over a dozen books, including the international bestseller Witness to Hope: The Biography of John Paul II, The Courage to be Catholic, Letters to a Young Catholic, The Cube and the Cathedral, and God's Choice. He lives in North Bethesda, Maryland.